Cosimo I and Eleonora of Toledo

The story of the palace comes to life again in the middle of the sixteenth century with the figures of Cosimo I and his wife, Eleonora of Toledo.

Cosimo de’Medici claimed a distinguished heritage, uniting both important fifteenth-century branches of the Medici family. His mother, Maria Salviati, was the granddaughter of Lorenzo the Magnificent through her mother, Lucrezia, while his father was Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, son of Caterina Sforza and Giovanni il Popolano who was a descendant of the younger branch of the family. Cosimo became the second Duke of Florence at the age of eighteen upon the assassination of his cousin the first duke of Florence, Alessandro.

Despite his distinguished lineage Cosimo had been raised in the countryside of the Mugello as far from the intrigues of Alessandro’s court in Florence as his mother could arrange. His principal goal upon his ascension to the throne was to solidify his position both within Florence and in Europe more broadly. Finding an appropriate wife was thus essential. Originally, Cosimo hoped to marry Margaret of Austria, the widow of his cousin Duke Alessandro, but the lady was very reluctant as was her father, the Emperor Charles V, who offered instead the hand of one of the daughters of the rich Spanish viceroy in Naples, and Cosimo agreed.

Cosimo de’Medici claimed a distinguished heritage, uniting both important fifteenth-century branches of the Medici family. His mother, Maria Salviati, was the granddaughter of Lorenzo the Magnificent through her mother, Lucrezia, while his father was Giovanni dalle Bande Nere, son of Caterina Sforza and Giovanni il Popolano who was a descendant of the younger branch of the family. Cosimo became the second Duke of Florence at the age of eighteen upon the assassination of his cousin the first duke of Florence, Alessandro.

Despite his distinguished lineage Cosimo had been raised in the countryside of the Mugello as far from the intrigues of Alessandro’s court in Florence as his mother could arrange. His principal goal upon his ascension to the throne was to solidify his position both within Florence and in Europe more broadly. Finding an appropriate wife was thus essential. Originally, Cosimo hoped to marry Margaret of Austria, the widow of his cousin Duke Alessandro, but the lady was very reluctant as was her father, the Emperor Charles V, who offered instead the hand of one of the daughters of the rich Spanish viceroy in Naples, and Cosimo agreed.

Cosimo I and Eleonora of Toledo were married by proxy on 29 March 1539 and lived happily together until her death in Pisa in 1562. After their marriage Cosimo and Eleonora lived in the Medici family palace on Via Larga until they moved into quarters prepared for them by Giorgio Vasari in Palazzo Vecchio. While Eleonora ultimately had eleven children, ten of whom survived, seven of her children shared their parents’ quarters in Palazzo Vecchio in 1549. It is no wonder that Eleonora was anxious to find more suitable quarters for her large family as well as access to fresh air and the countryside. In that year Eleonora purchased Palazzo Pitti from Buonaccorso Pitti, a descendant of Luca Pitti. Eleonora’s acquisition is cited as “the Pitti’s palace and orchard” and consisted of:

"A large palace; a house seu domibus retro (the house behind) called the "old" house; a piazza in front; a courtyard; loggia, piazzas, fountains; and other rights and easements. It also included the large orchard that extended from the palace to the Florentine walls, including about 146 staiora (an early Tuscan unit of measurement for area)."

The Pitti property met another important requirement: it included a large seigniorial residence set in ample gardens, and above all, it was protected along all its borders by the walls of convents, the ancient city wall, and in the south, by the ramparts that Cosimo had constructed during the war with Siena. There was no urban development outside those walls, permitting a quick exit from the city.

The size of the property was later increased by the acquisition of two additional farms, one in 1550 from the monks of Santa Felicita and the other in 1551 from Guidi di Monterigol.

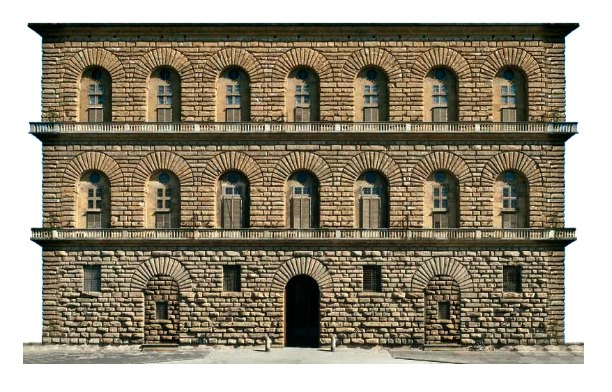

The documentary sources dating from 1552 to 1559 allow us to understand the original condition of Luca Pitti’s palace. The imposing façade realized in rough-hewn stone consisted of three equal stories. The two upper stories consisted of seven windows with fan-shaped arches also in rough-hewn stone. The ground floor had three identical openings, a central one with two symmetrical openings on the sides. Between them are four high, rectangular windows. By Eleonora’s time the two side entrances were walled up with rough stone, each with a small window. These were enriched by architectural elements added by Ammannati thirty years later. In the center of the two upper floors, the three central windows were open, but by 1557 those on the first floor facing the piazza were glassed in, the first such windows in Florence. Even so, they did not detract from the original chromatic function. At the time of acquisition, only the balcony and walkway on the first floor existed.

"A large palace; a house seu domibus retro (the house behind) called the "old" house; a piazza in front; a courtyard; loggia, piazzas, fountains; and other rights and easements. It also included the large orchard that extended from the palace to the Florentine walls, including about 146 staiora (an early Tuscan unit of measurement for area)."

The Pitti property met another important requirement: it included a large seigniorial residence set in ample gardens, and above all, it was protected along all its borders by the walls of convents, the ancient city wall, and in the south, by the ramparts that Cosimo had constructed during the war with Siena. There was no urban development outside those walls, permitting a quick exit from the city.

The size of the property was later increased by the acquisition of two additional farms, one in 1550 from the monks of Santa Felicita and the other in 1551 from Guidi di Monterigol.

The documentary sources dating from 1552 to 1559 allow us to understand the original condition of Luca Pitti’s palace. The imposing façade realized in rough-hewn stone consisted of three equal stories. The two upper stories consisted of seven windows with fan-shaped arches also in rough-hewn stone. The ground floor had three identical openings, a central one with two symmetrical openings on the sides. Between them are four high, rectangular windows. By Eleonora’s time the two side entrances were walled up with rough stone, each with a small window. These were enriched by architectural elements added by Ammannati thirty years later. In the center of the two upper floors, the three central windows were open, but by 1557 those on the first floor facing the piazza were glassed in, the first such windows in Florence. Even so, they did not detract from the original chromatic function. At the time of acquisition, only the balcony and walkway on the first floor existed.

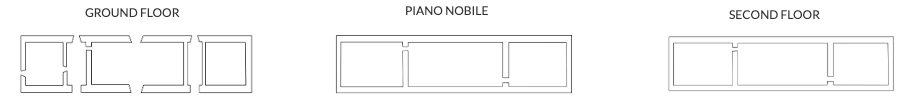

The interior of Luca Pitti’s palace begins to take shape in the workbooks from the sixteenth century. We can reconstruct the plan for the ground floor including the original elements that can be rediscovered in some of the elements of today’s palace. There was a large room with the central arch and two windows. There were then two symmetrical corridors covered by barrel vaults and then two more symmetrical rooms covered by cross vaults. The piano nobile consisted of a central room corresponding to the room on the ground floor, flanked symmetrically by two additional rooms. The second floor is explicitly described by Davide di Raffaaello Fortini, the first architect involved, as “…non v’era se nonenon e muri madornali sanza tramezi sanza usci finestre schale et alter loro appartenenze.”

Since the palace itself was largely unfinished at the time it was acquired by Eleonora, she concentrated much of her efforts on the “old” house. This house, with its loggia and its courtyard, appears in the archives of the Pitti family as a seigniorial residence located in a position perpendicular to but independent from Luca’s new palace. Most likely, it contained significant spaces and features that Duchess Eleonora wanted to maintain. Accordingly, she decided to connect the “old house” to the new palazzo with a new staircase and some new rooms that are described in contemporary documents as “new rooms between the old house and the palace.” The new palace, thus unified with the “old” house and enriched by friezes painted by Vasari and Bernardo Buontalenti, is represented in the fresco painted by Vasari in Clement VII’s room in Palazzo Vecchio, illustrating the Siege of Florence (1529-1530).

See also:

Emanuela Ferretti, "Palazzo Pitti 1550 - 1560 : precisazioni e nuove acquisizioni sui lavori di Eleonora di Toledo"; Opus incertum, 1, 1, 2006, pp 45-56.

Emanuela Ferretti, "Palazzo Pitti 1550 - 1560 : precisazioni e nuove acquisizioni sui lavori di Eleonora di Toledo"; Opus incertum, 1, 1, 2006, pp 45-56.